menu

Menu

Instead of a Foreword, a Fore-story

The Memory Genius

Then, Pillsbury began to play several blind games simultaneously. As a teenager, he had gained his first renown in America by playing three or four games at one go. He had learnt to play chess relatively late, at the age of sixteen. But after three years he was already known among insiders to be a future champion. In the spring of 1895, at the age of 22, Pillsbury was invited to the ‘Grand International Chess Tournament’ in Hastings (England) – the greatest tournament in chess history up till that time. World champion Emanuel Lasker, former world champion Wilhelm Steinitz as well as all top players from three generations had gathered to participate in this historic challenge. Pillsbury lost against Lasker, but this was only a minor setback for him. During one phase of the tournament he won nine games in a row, and so, at the end, he emerged victorious. The sensation was perfect.

Pillsbury became one of the first professional chess players of his time. Due to his victory in Hastings he was qualified to take part in the challenge tournament of St Petersburg (1895/6), where the three top world-championship candidates and Lasker had to play six games against each other. After the first half, Pillsbury was sovereignly leading. He had defeated Lasker twice, with one game drawn! In the fourth round, Lasker defeated Pillsbury in a spectacular way. The second half became a fiasco for Pillsbury. He lost all his games except for three draws (two against Lasker). The world champion ended this competition as clear winner, two points ahead of Steinitz, 3½ ahead of Pillsbury and 4½ ahead of Tchigorin.

In the following tournament of Nuremberg 1896, Pillsbury again defeated Lasker, who won the tournament nonetheless. A strange destiny followed Pillsbury: during some games he lost his famed concentration, which caused him to ruin even won positions. Thus, he spoiled one tournament victory after the other. These sometimes incomprehensible errors as well as his habit of incessantly smoking cigars hinted at something that was deeply gnawing within this young man …

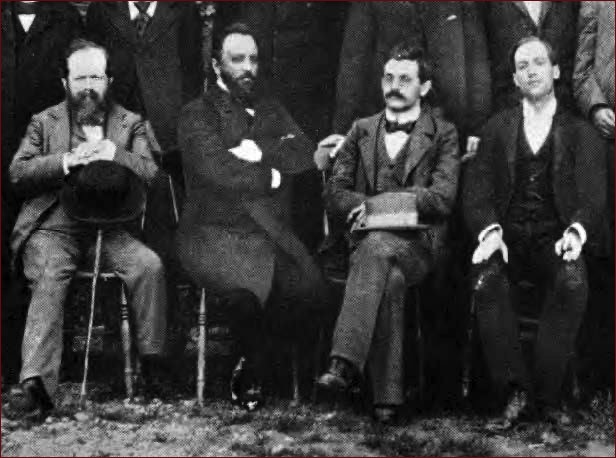

An example of a person with a photographic memory: 22-year old Harry Nelson Pillsbury (on the right, with cigar in hand), at the beginning of his short, comet-like career; here as the winner of the tournament in Hastings in 1895. Next to him world champion Emanuel Lasker, Russia’s No. 1 Mikhail Tchigorin and former world champion Wilhelm Steinitz.

Being in constant need of money, and perhaps also as a challenge to Lasker, Pillsbury (in addition to normal chess) made pioneering experiments in simultaneous blind chess. Travelling from one event to the next, he popularized chess and attracted the masses. In 1900, he went on a seven-month US tour, covering 40,000 miles, with over 150 performances. In 1897, he had become the official US chess champion. And now, this famous Harry Nelson Pillsbury stood on the stage, self-confident, and ready for the show – because as a show-act it had been announced: a performance of simultaneous blind chess and checkers, ten games of each, along with a surprise memory test! Clamorous applause, then again hushed silence. A member of the jury stepped forward and handed Pillsbury a piece of paper with a strange ‘poem’ to memorize:

Antiphlogistine, periosteum, takadiastase, plasmon, ambrosia, Threlkeld, streptococcus, staphylococcus, micrococcus, plasmodium, Mississippi, Freiheit, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, athletics, no war, Etchenberg, American, Russian, philosophy, Piet Potgelter’s Rost, Salamagundi, Oomisillecootsi, Bangmamvate, Schlechter’s Nek, Manzinyama, theosophy, catechism, Madjesoomalops

Two psychologists had compiled this nonsensical list with the intention of confusing Pillsbury’s memory with known and unknown terms. Unimpressed, Pillsbury read the paper while printed copies were being handed out to the audience. However, the last spectators in the back rows had not yet received the leaflet when Pillsbury laid his sheet aside and repeated the words from beginning to end and, for fun, also backwards. The audience was stunned.

Pillsbury seated himself at a small vacant table while twenty local players of chess and checkers were sitting along a row of tables a few metres away from him, with the boards placed in front of them. One player after the other made his move, which was conveyed to Pillsbury who, after short thought, announced his move. Then his respective opponent was given time to think until Pillsbury had made his next move in all other games. Sporadically he went to another table for some whist drives – just to make the show even more exciting, and also to give his opponents more time to think about their next moves. …

… continued in TranscEnding the Global Power Game, p. 13

Antiphlogistine, periosteum, takadiastase, plasmon, ambrosia, Threlkeld, streptococcus, staphylococcus, micrococcus, plasmodium, Mississippi, Freiheit, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, athletics, no war, Etchenberg, American, Russian, philosophy, Piet Potgelter’s Rost, Salamagundi, Oomisillecootsi, Bangmamvate, Schlechter’s Nek, Manzinyama, theosophy, catechism, Madjesoomalops

Two psychologists had compiled this nonsensical list with the intention of confusing Pillsbury’s memory with known and unknown terms. Unimpressed, Pillsbury read the paper while printed copies were being handed out to the audience. However, the last spectators in the back rows had not yet received the leaflet when Pillsbury laid his sheet aside and repeated the words from beginning to end and, for fun, also backwards. The audience was stunned.

Pillsbury seated himself at a small vacant table while twenty local players of chess and checkers were sitting along a row of tables a few metres away from him, with the boards placed in front of them. One player after the other made his move, which was conveyed to Pillsbury who, after short thought, announced his move. Then his respective opponent was given time to think until Pillsbury had made his next move in all other games. Sporadically he went to another table for some whist drives – just to make the show even more exciting, and also to give his opponents more time to think about their next moves. …

… continued in TranscEnding the Global Power Game, p. 13

© 1992 – 2024 Armin Risi

Home | Aktuell/Neu | Bücher | DVDs | Artikel | Biographie & Bibliographie | Veranstaltungen

quadratisch.jpg)